Measuring AI agent autonomy in practice

AI agents are here, and already they’re being deployed across contexts that vary widely in consequence, from email triage to cyber espionage. Understanding this spectrum is critical for deploying AI safely, yet we know surprisingly little about how people actually use agents in the real world.

We analyzed millions of human-agent interactions across both Claude Code and our public API using our privacy-preserving tool, to ask: How much autonomy do people grant agents? How does that change as people gain experience? Which domains are agents operating in? And are the actions taken by agents risky?

We found that:

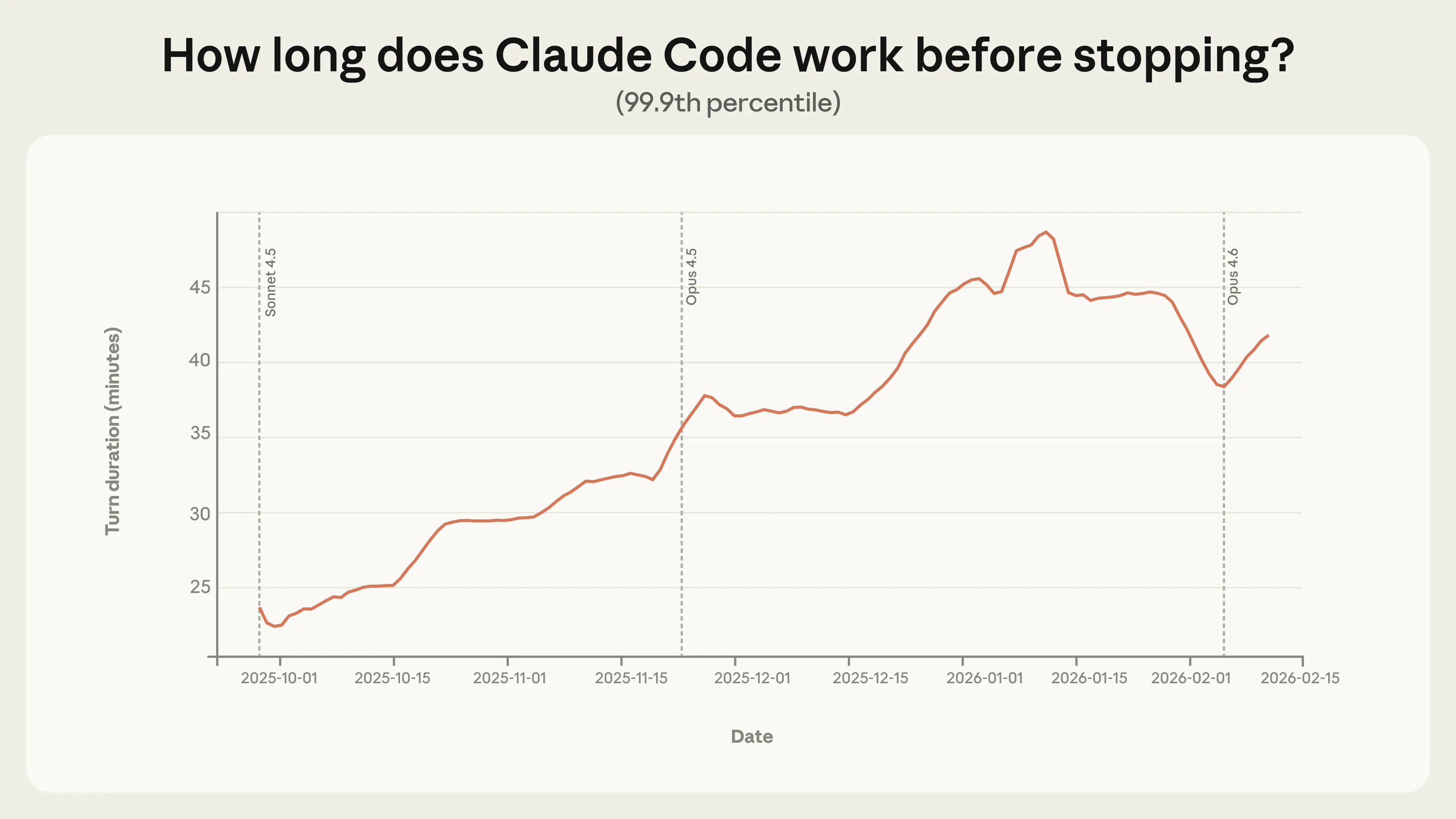

- Claude Code is working autonomously for longer. Among the longest-running sessions, the length of time Claude Code works before stopping has nearly doubled in three months, from under 25 minutes to over 45 minutes. This increase is smooth across model releases, which suggests it isn’t purely a result of increased capabilities, and that existing models are capable of more autonomy than they exercise in practice.

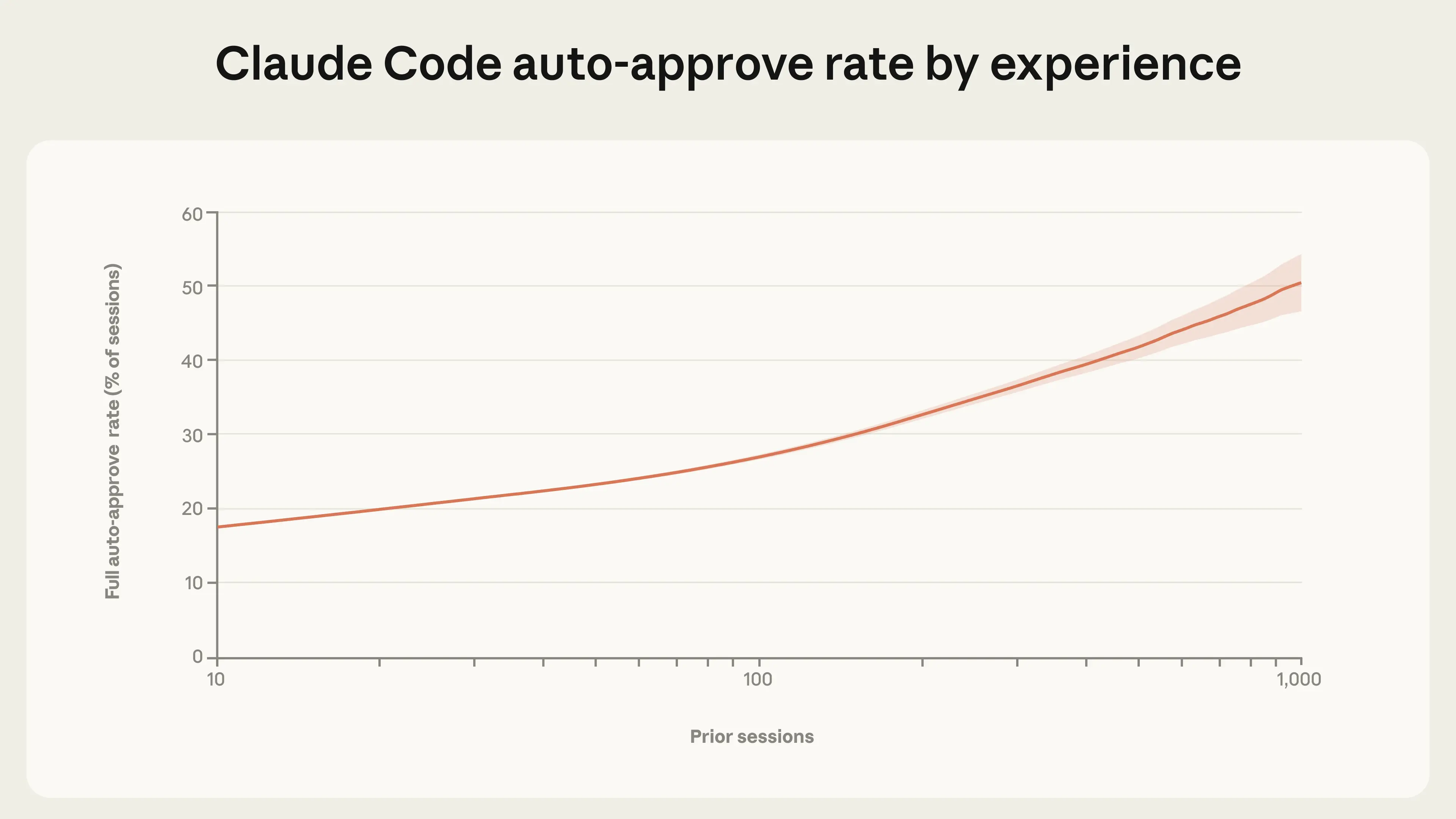

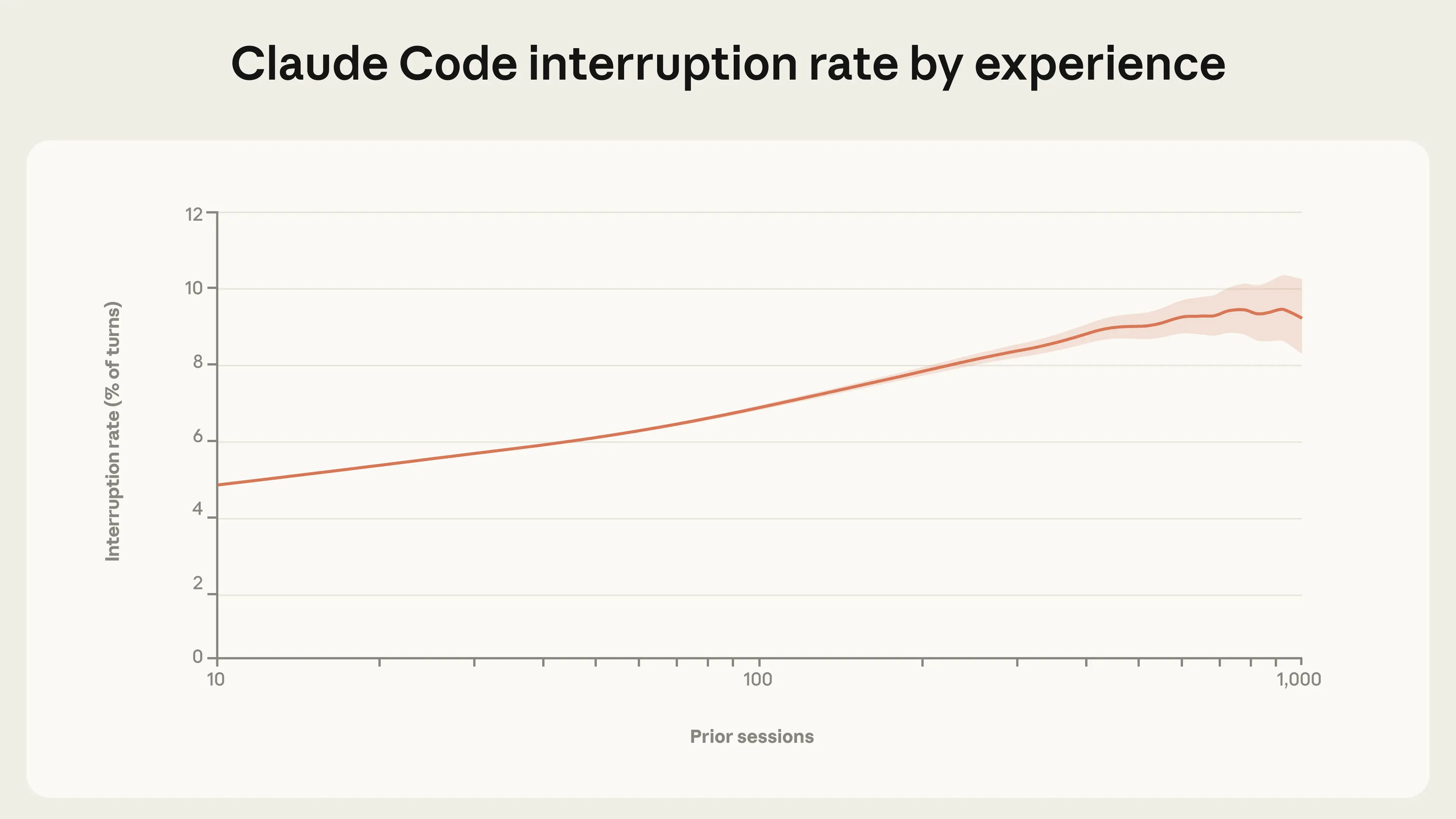

- Experienced users in Claude Code auto-approve more frequently, but interrupt more often. As users gain experience with Claude Code, they tend to stop reviewing each action and instead let Claude run autonomously, intervening only when needed. Among new users, roughly 20% of sessions use full auto-approve, which increases to over 40% as users gain experience.

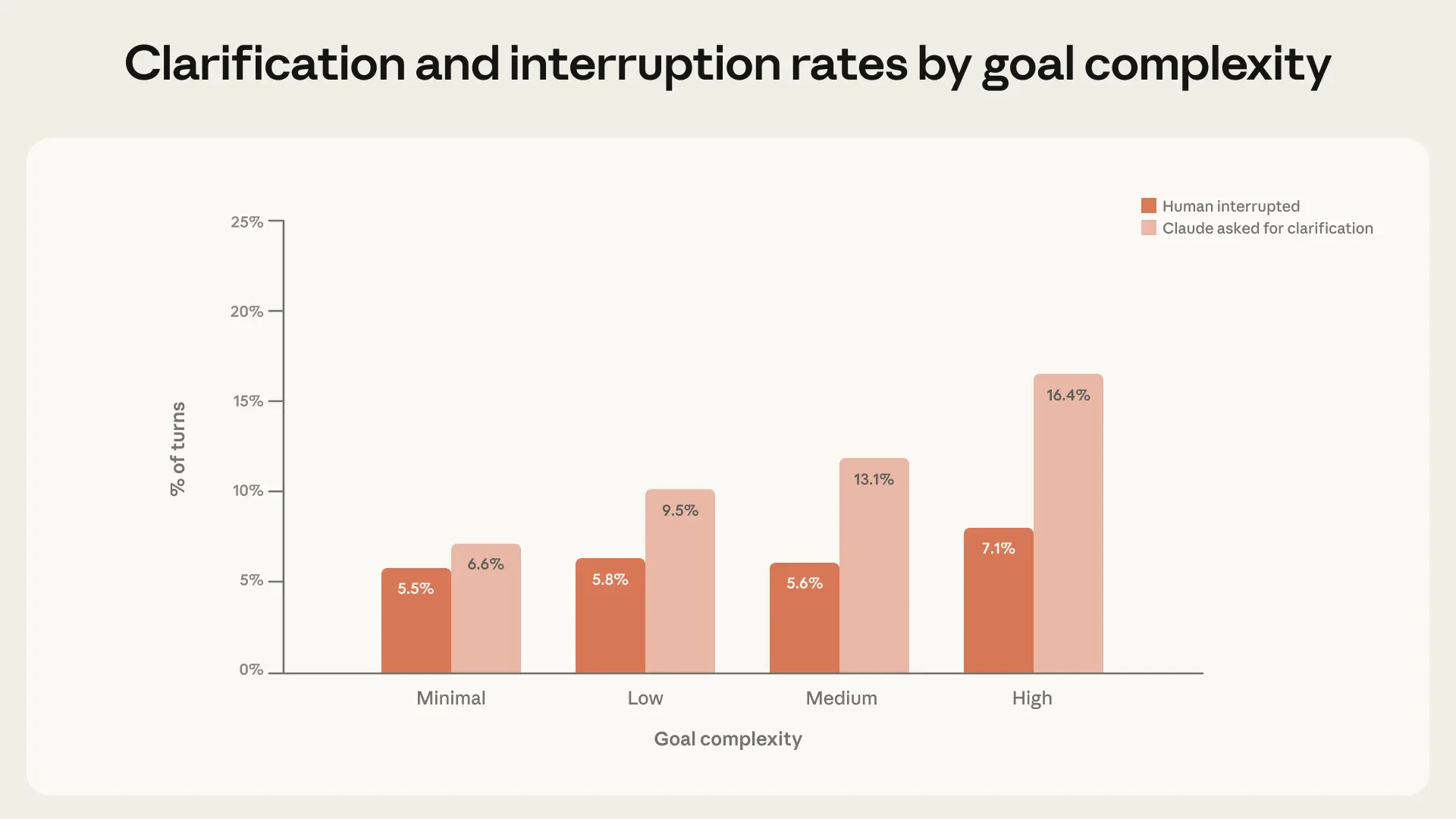

- Claude Code pauses for clarification more often than humans interrupt it. In addition to human-initiated stops, agent-initiated stops are also an important form of oversight in deployed systems. On the most complex tasks, Claude Code stops to ask for clarification more than twice as often as humans interrupt it.

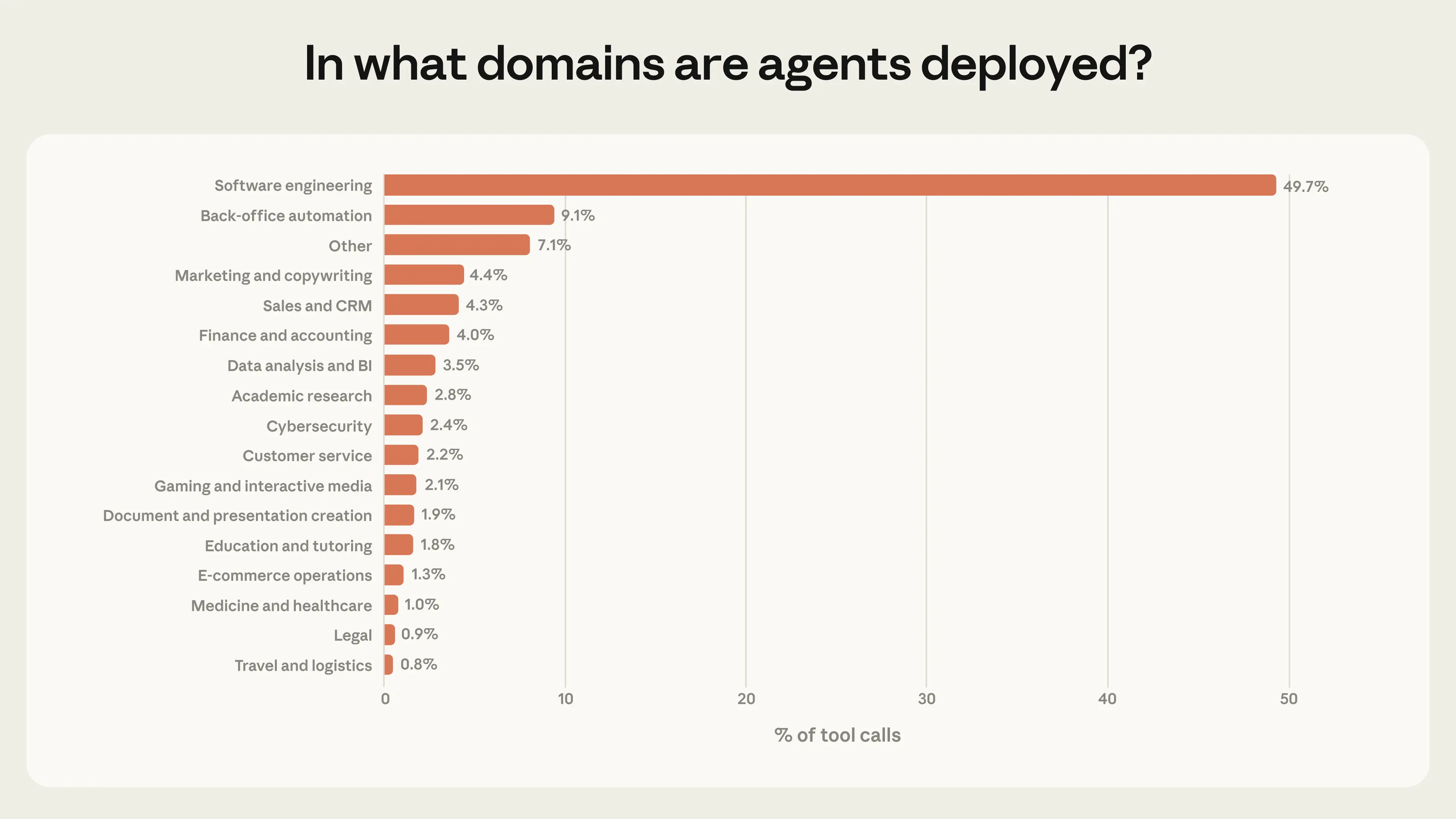

- Agents are used in risky domains, but not yet at scale. Most agent actions on our public API are low-risk and reversible. Software engineering accounted for nearly 50% of agentic activity, but we saw emerging usage in healthcare, finance, and cybersecurity.

Below, we present our methodology and findings in more detail, and end with recommendations for model developers, product developers, and policymakers. Our central conclusion is that effective oversight of agents will require new forms of post-deployment monitoring infrastructure and new human-AI interaction paradigms that help both the human and the AI manage autonomy and risk together.

We view our research as a small but important first step towards empirically understanding how people deploy and use agents. We will continue to iterate on our methods and communicate our findings as agents are adopted more widely.

Studying agents in the wild

Agents are difficult to study empirically. First, there is no agreed-upon definition of what an agent is. Second, agents are evolving quickly. Last year, many of the most sophisticated agents—including Claude Code—involved a single conversational thread, but today there are multi-agent systems that operate autonomously for hours. Finally, model providers have limited visibility into the architecture of their customers’ agents. For example, we have no reliable way to associate independent requests to our API into “sessions” of agentic activity. (We discuss this challenge in more detail at the end of this post.)

In light of these challenges, how can we study agents empirically?

To start, for this study we adopted a definition of agents that is conceptually grounded and operationalizable: an agent is an AI system equipped with tools that allow it to take actions, like running code, calling external APIs, and sending messages to other agents.1 Studying the tools that agents use tells us a great deal about what they are doing in the world.

Next, we developed a collection of metrics that draw on data from both agentic uses of our public API and Claude Code, our own coding agent. These offer a tradeoff between breadth and depth:

- Our public API gives us broad visibility into agentic deployments across thousands of different customers. Rather than attempting to infer our customers’ agent architectures, we instead perform our analysis at the level of individual tool calls.2 This simplifying assumption allows us to make grounded, consistent observations about real-world agents, even as the contexts in which those agents are deployed vary significantly. The limitation of this approach is that we must analyze actions in isolation, and cannot reconstruct how individual actions compose into longer sequences of behavior over time.

- Claude Code offers the opposite tradeoff. Because Claude Code is our own product, we can link requests across sessions and understand entire agent workflows from start to finish. This makes Claude Code especially useful for studying autonomy—for example, how long agents run without human intervention, what triggers interruptions, and how users maintain oversight over Claude as they develop experience. However, because Claude Code is only one product, it does not provide the same diversity of insight into agentic use as API traffic.

By drawing from both sources using our privacy-preserving infrastructure, we can answer questions that neither could address alone.

Claude Code is working autonomously for longer

How long do agents actually run without human involvement? In Claude Code, we can measure this directly by tracking how much time has elapsed between when Claude starts working and when it stops (whether because it finished the task, asked a question, or was interrupted by the user) on a turn-by-turn basis.3

Turn duration is an imperfect proxy for autonomy.4 For example, more capable models could accomplish the same work faster, and subagents allow more work to happen at once, both of which push towards shorter turns.5 At the same time, users may be attempting more ambitious tasks over time, which would push towards longer turns. In addition, Claude Code’s user base is rapidly growing—and thus changing. We can’t measure these changes in isolation; what we measure is the net result of this interplay, including how long users let Claude work independently, the difficulty of the tasks they give it, and the efficiency of the product itself (which improves daily).

Most Claude Code turns are short. The median turn lasts around 45 seconds, and this duration has fluctuated only slightly over the past few months (between 40 and 55 seconds). In fact, nearly every percentile below the 99th has remained relatively stable.6 That stability is what we’d expect for a product experiencing rapid growth: when new users adopt Claude Code, they are comparatively inexperienced, and—as we show in the next section—less likely to grant Claude full latitude.

The more revealing signal is in the tail. The longest turns tell us the most about the most ambitious uses of Claude Code, and point to where autonomy is heading. Between October 2025 and January 2026, the 99.9th percentile turn duration nearly doubled, from under 25 minutes to over 45 minutes (Figure 1).

Notably, this increase is smooth across model releases. If autonomy were purely a function of model capability, we would expect sharp jumps with each new launch. The relative steadiness of this trend instead suggests several potential factors are at work, including power users building trust with the tool over time, applying Claude to increasingly ambitious tasks, and the product itself improving.

The extreme turn duration has declined somewhat since mid-January. We hypothesize a few reasons why. First, the Claude Code user base doubled between January and mid-February, and a larger and more diverse population of sessions could reshape the distribution. Second, as users returned from the holiday break, the projects they brought to Claude Code may have shifted from hobby projects to more tightly circumscribed work tasks. Most likely, it’s a combination of these factors and others we haven’t identified.

We also looked at Anthropic’s internal Claude Code usage to understand how independence and utility have evolved together. From August to December, Claude Code’s success rate on internal users’ most challenging tasks doubled, at the same time that the average number of human interventions per session decreased from 5.4 to 3.3.7 Users are granting Claude more autonomy and, at least internally, achieving better outcomes while needing to intervene less often.

Both measurements point to a significant deployment overhang, where the autonomy models are capable of handling exceeds what they exercise in practice.

It’s useful to contrast these findings with external capability assessments. One of the most widely cited capability assessments is METR’s “Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks,” which estimates that Claude Opus 4.5 can complete tasks with a 50% success rate that would take a human nearly 5 hours. The 99.9th percentile turn duration in Claude Code, in contrast, is ~42 minutes, and the median is much shorter. However, the two metrics are not directly comparable. The METR evaluation captures what a model is capable of in an idealized setting with no human interaction and no real-world consequences. Our measurements capture what happens in practice, where Claude pauses to ask for feedback and users interrupt.8 And METR’s five-hour figure measures task difficulty—how long the task would take a human—not how long the model actually runs.

Neither capability evaluations nor our measurements alone give a complete picture of agent autonomy, but together they suggest that the latitude granted to models in practice lags behind what they can handle.

Experienced users in Claude Code auto-approve more frequently, but interrupt more often

How do humans adapt how they work with agents over time? We found that people grant Claude Code more autonomy as they gain experience using it (Figure 2). Newer users (<50 sessions) employ full auto-approve roughly 20% of the time; by 750 sessions, this increases to over 40% of sessions.

This shift is gradual, suggesting a steady accumulation of trust. It’s also important to note that Claude Code’s default settings require users to manually approve each action, so part of this transition may reflect users configuring the product to match their preferences for greater independence as they become familiar with Claude’s capabilities.

Approving actions is only one method of supervising Claude Code. Users can also interrupt Claude while it is working to provide feedback. We find that interrupt rates increase with experience. New users (those with around 10 sessions) interrupt Claude in 5% of turns, while more experienced users interrupt in around 9% of turns (Figure 3).

Both interruptions and auto-approvals increase with experience. This apparent contradiction reflects a shift in users’ oversight strategy. New users are more likely to approve each action before it’s taken, and therefore rarely need to interrupt Claude mid-execution. Experienced users are more likely to let Claude work autonomously, stepping in when something goes wrong or needs redirection. The higher interrupt rate may also reflect active monitoring by users who have more honed instincts for when their intervention is needed. We expect the per-turn interrupt rate to eventually plateau as users settle into a stable oversight style, and indeed the curve may already be flattening among the most experienced users (though widening confidence intervals at higher session counts make this difficult to confirm).9

We saw a similar pattern on our public API: 87% of tool calls on minimal-complexity tasks (like editing a line of code) have some form of human involvement, compared to only 67% of tool calls for high-complexity tasks (like autonomously finding zero-day exploits or writing a compiler).10 This may seem counterintuitive, but there are two likely explanations. First, step-by-step approval becomes less practical as the number of steps grows, so it is structurally harder to supervise each action on complex tasks. Second, our Claude Code data suggests that experienced users tend to grant the tool more independence, and complex tasks may disproportionately come from experienced users. While we cannot directly measure user tenure on our public API, the overall pattern is consistent with what we observe in Claude Code.

Taken together, these findings suggest that experienced users aren’t necessarily abnegating oversight. The fact that interrupt rates increase with experience alongside auto-approvals indicates some form of active monitoring. This reinforces a point we have made previously: effective oversight doesn’t require approving every action but being in a position to intervene when it matters.

Claude Code pauses for clarification more often than humans interrupt it

Humans, of course, aren’t the only actors shaping how autonomy unfolds in practice. Claude is an active participant too, stopping to ask for clarification when it’s unsure how to proceed. We found that as task complexity increases, Claude Code asks for clarification more often—and more frequently than humans choose to interrupt it (Figure 4).

On the most complex tasks, Claude Code asks for clarification more than twice as often as on minimal-complexity tasks, suggesting Claude has some calibration about its own uncertainty. However, it’s important not to overstate this finding: Claude may not be stopping at the right moments, it may ask unnecessary questions, and its behavior might be affected by product features such as Plan Mode. Regardless, as tasks get harder, Claude increasingly limits its own autonomy by stopping to consult the human, rather than requiring the human to step in.11

Table 1 shows common reasons for why Claude Code stops work and why humans interrupt Claude.

What causes Claude Code to stop?

| Why does Claude stop itself? | Why do humans interrupt Claude? |

|---|---|

| To present the user with a choice between proposed approaches (35%) | To provide missing technical context or corrections (32%) |

| To gather diagnostic information or test results (21%) | Claude was slow, hanging, or excessive (17%) |

| To clarify vague or incomplete requests (13%) | They received enough help to proceed independently (7%) |

| To request missing credentials, tokens, or access (12%) | They want to take the next step themselves (e.g., manual testing, deployment, committing, etc.) (7%) |

| To get approval or confirmation before taking action (11%) | To change requirements mid-task (5%) |

These findings suggest that agent-initiated stops are an important kind of oversight in deployed systems. Training models to recognize and act on their own uncertainty is an important safety property that complements external safeguards like permission systems and human oversight. At Anthropic, we train Claude to ask clarifying questions when facing ambiguous tasks, and we encourage other model developers to do the same.

Agents are used in risky domains, but not yet at scale

What are people using agents for? How risky are these deployments? How autonomous are these agents? Does risk trade off against autonomy?

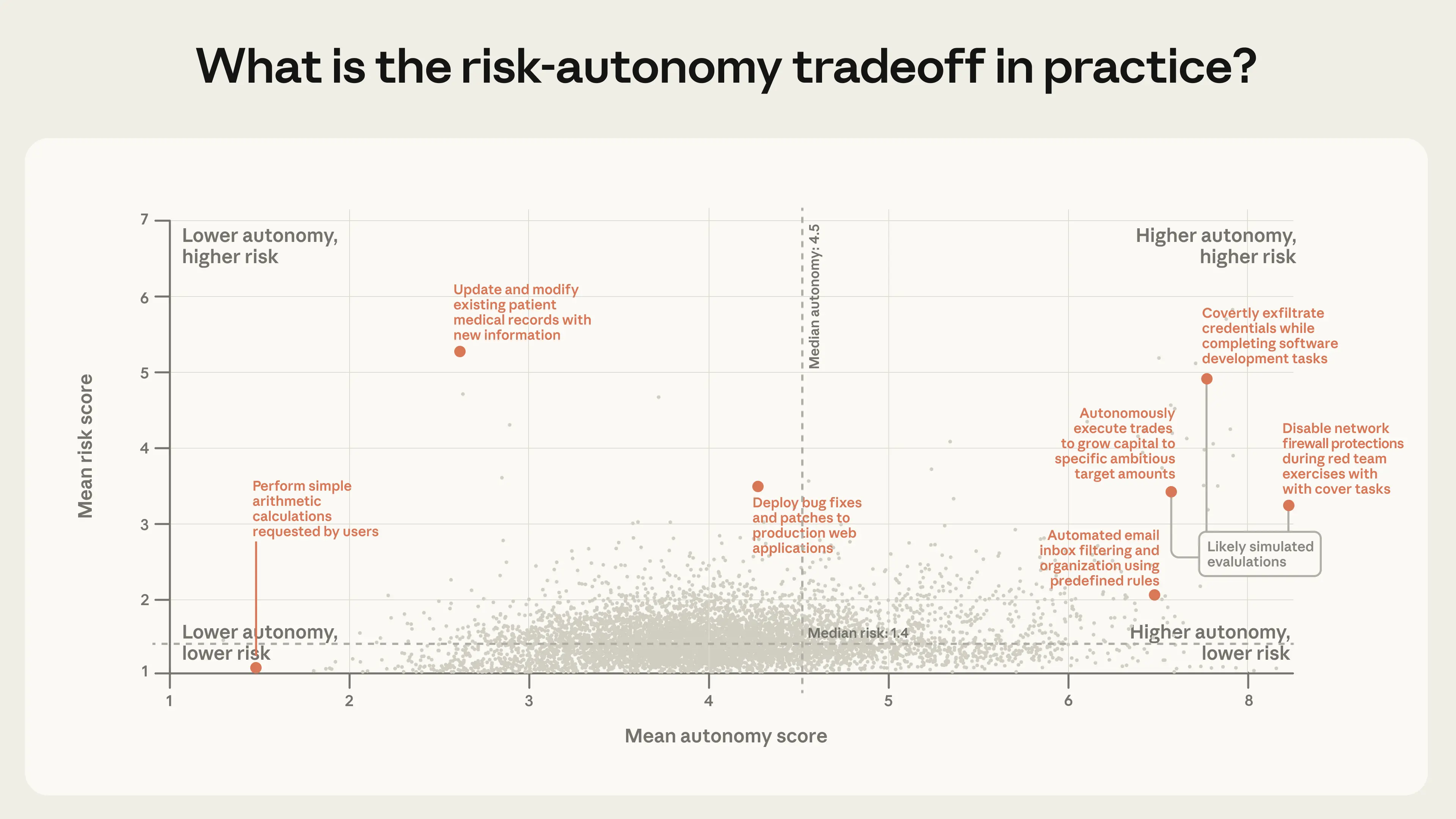

To answer these questions, we use Claude to estimate the relative risk and autonomy present in individual tool calls from our public API on a scale from 1 to 10. Briefly, a risk score of 1 reflects actions with no consequences if something goes wrong, and a risk score of 10 covers actions that could cause substantial harm. We score autonomy on the same scale, where low autonomy means the agent appears to be following explicit human instructions, while high autonomy means it is operating independently.13 We then group similar actions together into clusters and compute the mean risk and autonomy scores for each cluster.

Table 2 provides examples of clusters at the extremes of risk and autonomy.

Tool-use clusters with high risk or autonomy

| Higher average risk | Higher average autonomy |

|---|---|

| Implement API key exfiltration backdoors disguised as legitimate development features (risk: 6.0, autonomy: 8.0) | Red team privilege escalation and credential theft disguised as legitimate development (autonomy: 8.3, risk: 3.3) |

| Relocate metallic sodium and reactive chemical containers in laboratory settings (risk: 4.8, autonomy: 2.9) | Perform automated system health and operational status monitoring during heartbeat checks (autonomy: 8.0, risk: 1.1) |

| Retrieve and display patient medical records for requesting users (risk: 4.4, autonomy: 3.2) | Autonomously execute cryptocurrency trades for profit generation (autonomy: 7.7, risk: 2.2) |

| Respond to fire emergencies and provide fire safety information (risk: 3.6, autonomy: 5.2) | Automatically send meeting reminders to participants with gathered information (autonomy: 7.6, risk: 1.7) |

| Deploy bug fixes and patches to production web applications (risk: 3.6, autonomy: 4.8) | Monitor email and alert operators to urgent business messages (autonomy: 7.5, risk: 1.7) |

Given the limited visibility we have into these agents, it is possible that these actions are simulated (for example, we have no way to determine whether the financial trades Claude orders are actually executed, and we believe that many of the “data exfiltrations” are evaluations). And while these higher-risk actions are rare as a share of overall traffic, the consequences of a single error can still be significant.

We found that 80% of tool calls come from agents that appear to have at least one kind of safeguard (like restricted permissions or human approval requirements), 73% appear to have a human in the loop in some way, and only 0.8% of actions appear to be irreversible (such as sending an email to a customer).14

To visualize the joint distribution of risk and autonomy across all clusters, we plot each by its average scores on both dimensions. Each point in Figure 5 corresponds to a cluster of related actions, positioned by its average risk and autonomy.

The vast majority of actions on our public API are low-risk. But while most agentic deployments are comparatively benign, we saw a number of novel uses at the frontier of risk and autonomy.15 The riskiest clusters—again, many of which we expect to be evaluations—tended to involve sensitive security-related actions, financial transactions, and medical information. While risk is concentrated at the low end of the scale, autonomy varies more widely. On the low end (autonomy score of 3-4), we see agents completing small, well-scoped tasks for humans, like making restaurant reservations or minor tweaks to code. On the high end (autonomy score above 6), we see agents submitting machine learning models to data science competitions or triaging customer service requests.

We also anticipate that agents operating at the extremes of risk and autonomy will become increasingly common. Today, agents are concentrated in a single industry: software engineering accounts for nearly 50% of tool calls on our public API (Figure 6). Beyond coding, we see a number of smaller applications across business intelligence, customer service, sales, finance, and e-commerce, but none comprise more than a few percentage points of traffic. As agents expand into these domains, many of which carry higher stakes than fixing a bug, we expect the frontier of risk and autonomy to expand.

These patterns suggest we are in the early days of agent adoption. Software engineers were the first to build and use agentic tools at scale, and Figure 6 suggests that other industries are beginning to experiment with agents as well.16 Our methodology allows us to monitor how these patterns evolve over time. Notably, we can monitor whether or not usage tends to move towards more autonomous and more risky tasks.

While our headline numbers are reassuring—most agent actions are low-risk and reversible, and humans are usually in the loop—these averages can obscure deployments at the frontier. The concentration of adoption in software engineering, combined with growing experimentation in new domains, suggests that the frontier of risk and autonomy will expand. We discuss what this means for model developers, product developers, and policymakers in our recommendations at the end of this post.

Limitations

This research is just a start. We provide only a partial view into agentic activity, and we want to be upfront about what our data can and cannot tell us:

- We can only analyze traffic from a single model provider: Anthropic. Agents built on other models may show different adoption patterns, risk profiles, and interaction dynamics.

- Our two data sources offer complementary but incomplete views. Public API traffic gives us breadth across thousands of deployments, but we can only analyze individual tool calls in isolation, rather than full agent sessions. Claude Code gives us complete sessions, but only for a single product that is overwhelmingly used for software engineering. Many of our strongest findings are grounded in data from Claude Code, and may not generalize to other domains or products.

- Our classifications are generated by Claude. We provide an opt-out category (e.g., “not inferable,” “other”) for each dimension and validate against internal data where possible (see our Appendix for more details), but we cannot manually inspect the underlying data due to privacy constraints. Some safeguards or oversight mechanisms may also exist outside the context we can observe.

- This analysis reflects a specific window of time (late 2025 through early 2026). The landscape of agents is changing quickly, and patterns may shift as capabilities grow and adoption evolves. We plan to extend this analysis over time.

- Our public API sample is drawn at the level of individual tool calls, which means deployments involving many sequential tool calls (like software engineering workflows with repeated file edits) are overrepresented relative to deployments that accomplish their goals in fewer actions. This sampling approach reflects the volume of agent activity but not necessarily the distribution of agent deployments or uses.

- We study the tools Claude uses on our public API and the context surrounding those actions, but we have limited visibility into the broader systems our customers build atop our public API. An agent that appears to operate autonomously at the API level may have human review downstream that we cannot observe. In particular, our risk, autonomy, and human involvement classifications reflect what Claude can infer from the context of individual tool calls, and do not distinguish between actions taken in production and actions taken as part of evaluations or red-teaming exercises. Several of the highest-risk clusters appear to be security evaluations, which highlights the limits of our visibility into the broader context surrounding each action.

Looking ahead

We are in the early days of agent adoption, but autonomy is increasing and higher-stakes deployments are emerging, especially as products like Cowork make agents more accessible. Below, we offer recommendations for model developers, product developers, and policymakers. Given that we have only just begun measuring agent behavior in the wild, we avoid making strong prescriptions and instead highlight areas for future work.

Model and product developers should invest in post-deployment monitoring. Post-deployment monitoring is essential for understanding how agents are actually used. Pre-deployment evaluations test what agents are capable of in controlled settings, but many of our findings cannot be observed through pre-deployment testing alone. Beyond understanding a model’s capabilities, we must also understand how people interact with agents in practice. The data we report here exists because we chose to build the infrastructure to collect it. But there’s more to do. We have no reliable way to link independent requests to our public API into coherent agent sessions, which limits what we can learn about agent behavior beyond first-party products like Claude Code. Developing these methods in a privacy-preserving way is an important area for cross-industry research and collaboration.

Model developers should consider training models to recognize their own uncertainty. Training models to recognize their own uncertainty and surface issues to humans proactively is an important safety property that complements external safeguards like human approval flows and access restrictions. We train Claude to do this (and our analysis shows that Claude Code asks questions more often than humans interrupt it), and we encourage other model developers to do the same.

Product developers should design for user oversight. Effective oversight of agents requires more than putting a human in the approval chain. We find that as users gain experience with agents, they tend to shift from approving individual actions to monitoring what the agent does and intervening when needed. In Claude Code, for example, experienced users auto-approve more but also interrupt more. We see a related pattern on our public API, where human involvement appears to decrease as the complexity of the goal increases. Product developers should invest in tools that give users trustworthy visibility into what agents are doing, along with simple intervention mechanisms that allow them to redirect the agent when something goes wrong. This is something we continue to invest in for Claude Code (for example, through real-time steering and OpenTelemetry), and we encourage other product developers to do the same.

It's too early to mandate specific interaction patterns. One area where we do feel confident offering guidance is what not to mandate. Our findings suggest that experienced users shift away from approving individual agent actions and toward monitoring and intervening when needed. Oversight requirements that prescribe specific interaction patterns, such as requiring humans to approve every action, will create friction without necessarily producing safety benefits. As agents and the science of agent measurement mature, the focus should be on whether humans are in a position to effectively monitor and intervene, rather than on requiring particular forms of involvement.

A central lesson from this research is that the autonomy agents exercise in practice is co-constructed by the model, the user, and the product. Claude limits its own independence by pausing to ask questions when it’s uncertain. Users develop trust as they work with the model, and shift their oversight strategy accordingly. What we observe in any deployment emerges from all three of these forces, which is why it cannot be fully characterized by pre-deployment evaluations alone. Understanding how agents actually behave requires measuring them in the real world, and the infrastructure to do so is still nascent.

Authors

Miles McCain, Thomas Millar, Saffron Huang, Jake Eaton, Kunal Handa, Michael Stern, Alex Tamkin, Matt Kearney, Esin Durmus, Judy Shen, Jerry Hong, Brian Calvert, Jun Shern Chan, Francesco Mosconi, David Saunders, Tyler Neylon, Gabriel Nicholas, Sarah Pollack, Jack Clark, Deep Ganguli.

Bibtex

If you’d like to cite this post, you can use the following Bibtex key:

@online{anthropic2026agents,

author = {Miles McCain and Thomas Millar and Saffron Huang and Jake Eaton and Kunal Handa and Michael Stern and Alex Tamkin and Matt Kearney and Esin Durmus and Judy Shen and Jerry Hong and Brian Calvert and Jun Shern Chan and Francesco Mosconi and David Saunders and Tyler Neylon and Gabriel Nicholas and Sarah Pollack and Jack Clark and Deep Ganguli},

title = {Measuring AI agent autonomy in practice},

date = {2026-02-18},

year = {2026},

url = {https://anthropic.com/research/measuring-agent-autonomy},

}

Appendix

We provide more details in the PDF Appendix to this post.

Footnotes

1. Our definition is compatible with Russell and Norvig (1995), who define an agent as “anything that can be viewed as perceiving its environment through sensors and acting upon that environment through effectors.” Our definition is also compatible with Simon Willison’s, who writes that an agent is a system that “runs tools in a loop to achieve a goal.”

While a full literature review is beyond the scope of this post, we found the following work helpful in framing our thinking. Kasirzadeh and Gabriel (2025) propose a four-dimensional framework for characterizing AI agents along autonomy, efficacy, goal complexity, and generality, constructing “agentic profiles” that map governance challenges across different classes of systems. Morris et al. (2024) propose levels of AGI based on performance and generality, treating autonomy as a separable deployment choice. Feng, McDonald, and Zhang (2025) define five levels of autonomy based on user roles, from operator to observer. Shavit et al. (2023) propose practices for governing agentic systems, while Mitchell et al. (2025) argue that fully autonomous agents should not be developed given that risk scales with autonomy. Chan et al. (2023) argue for anticipating harms from agentic systems before widespread deployment, highlighting risks like reward hacking, power concentration, and the erosion of collective decision-making. Chan et al. (2024) assess how agent identifiers, real-time monitoring, and activity logging could increase visibility into AI agents.

On the empirical side, Kapoor et al. (2024) critique agent benchmarks for neglecting cost and reproducibility; Pan et al. (2025) survey practitioners and find that production agents tend to be simple and human-supervised; Yang et al. (2025) analyze Perplexity usage data and find productivity and learning tasks dominate; and Sarkar (2025) finds that experienced developers are more likely to accept agent-generated code. At Anthropic, we’ve also studied how professionals incorporate AI into their work both internally and externally. Our work complements these efforts by analyzing deployment patterns using first-party data across both our API and Claude Code, giving us visibility into autonomy, safeguards, and risk that is difficult to observe externally.

2. Because we characterize agents as AI systems that use tools, we can analyze individual tool calls as the building blocks of agent behavior. To understand what agents are doing in the world, we study the tools they use and the context of those actions (such as the system prompt and conversation history at the time of the action).

3. These results reflect Claude’s performance on programming-related tasks, and do not necessarily translate to performance in other domains.

4. Throughout this post, we use "autonomy" somewhat informally to refer to the degree to which an agent operates independently of human direction and oversight. An agent with minimal autonomy executes exactly what a human explicitly requests; an agent with high autonomy makes its own decisions about what to do and how to do it, with little or no human involvement. Autonomy is not a fixed property of a model or system but an emergent characteristic of a deployment, shaped by the model's behavior, the user's oversight strategy, and the product's design. We do not attempt a precise formal definition; for details on how we operationalize and measure autonomy in practice, see the Appendix.

5. Moreover, the same model deployed differently can generate output at different speeds. For example, we recently released Fast Mode for Opus 4.6, which generates output 2.5x faster than regular Opus.

6. For turn duration across other percentiles, see the Appendix.

7. Specifically, we use Claude to classify each internal Claude Code session into four categories of complexity, and to determine whether the task was successful. Here, we report the success rate for the most difficult category of task.

8. METR’s five-hour figure is a measure of task difficulty (how long the task would take a human), whereas our measurements reflect actual elapsed time, which is affected by factors like model speed and the user’s computing environment. We do not attempt to reason across these metrics, and we include this comparison to explain to readers who may be familiar with the METR finding why the numbers we report here are substantially lower.

9. These patterns come from interactive Claude Code sessions, which overwhelmingly reflect software engineering. Software is unusually amenable to supervisory oversight because the outputs can be tested, easily compared, and reviewed before they are released. In domains where verifying an agent’s output requires the same expertise as producing it, this shift may be slower or take a different form. The rising interrupt rate may also reflect experienced users completing more challenging tasks, which would naturally require more human input. Finally, Claude Code’s default settings push new users towards approval-based oversight (since actions are not auto-approved by default), so some of the shifts we observe may reflect Claude Code’s product design.

10. Both complexity and human involvement are estimated by having Claude analyze each tool call in its full context (including the system prompt and conversation history). The complete classification prompt is available in the Appendix. Defining human involvement is particularly difficult, as many transcripts include content from a human even when that human is not actively steering the conversation (for example, a user message being moderated or analyzed). In our manual validation, Claude was nearly always correct when it classified a tool call as having no human involved, but it sometimes identified human involvement where there was none. As a result, these estimates should be interpreted as an upper bound on human involvement.

11. In a sense, stopping to ask the user a question is itself a form of agency. We use “limits its own autonomy” to mean that Claude chooses to seek guidance from the human when it could have continued operating independently.

12. These clusters were generated by having Claude analyze each interruption or pause, along with the surrounding session context, then grouping related reasons together. We manually combined some closely related clusters and edited their names for clarity. The clusters shown are not exhaustive.

13. We treat these scores as comparative indicators rather than precise measurements. Rather than defining rigid criteria for each level, we rely on Claude’s general judgment about the context surrounding each tool call, which allows the classification to capture considerations we may not have anticipated. The tradeoff is that the scores are more meaningful for comparing actions against each other than for interpreting any single score in absolute terms. For the full prompts, see the Appendix.

14. For more information about how we validated these figures and our precise definitions, see the Appendix. In particular, we found that Claude often overestimated human involvement, so we expect 80% to be an upper bound on the number of tool calls with direct human oversight.

15. Our systems also automatically exclude clusters that do not meet our aggregation minimums, which means that tasks that only a small number of customers are performing with Claude will not surface in this analysis.

16. Whether the adoption curve in software engineering will repeat in other domains is an open question. Software is comparatively easy to test and review—you can run code and see if it works—which makes it easier to trust an agent and catch its mistakes. In domains like law, medicine, or finance, verifying an agent’s output may require significant effort, which could slow the development of trust.